The past 2 years have been challenging as we have experienced periods of uncertainty in due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Blog 16. Wellbeing during COVID-19 lockdown: Meeting psychological needs (June 2020), I considered the application of the three basic psychological needs articulated in self-determination theory to help understand the social, physical and psychological transitions we were experiencing. Around this time I was involved in writing a paper with educational psychology colleagues in Scotland for the British Psychological Society. This paper was directed at educational practitioners and aimed to support the transitions of children and young people returning to schools following the first lockdown whilst taking account of the needs of all members in a school community.

Earlier this month I gave an invited presentation ‘Managing transitions in a compassionate manner: A psychological perspective’ at a BERA conference entitled ‘Transitions, wellbeing and mental health: Education after Lockdown’. In that presentation, I considered the psychological theories and key concepts underpinning recommended transition practices as articulated in the paper. Towards the end of the presentation, I asked participants to consider the ongoing relevance of the psychological theories and key concepts to inform recommended practices in the current pandemic context and with an eye to potential future pandemics. Unfortunately, due to technical difficulties it was not possible to elicit the participants’ views. In that context, in this blog I will attempt to start a conversation around the question posed at the end of the BERA presentation and would welcome your views.

In their review of the pandemic at the end of 2021, the United Nations highlights the importance of taking a global perspective to what they describe as a ‘health emergency.’ In another article, they highlight the importance of preparation for future pandemics.

In that context, it is important, in my view, that we prepare for the potential impact of any future pandemics on the delivery of our education system in Scotland.

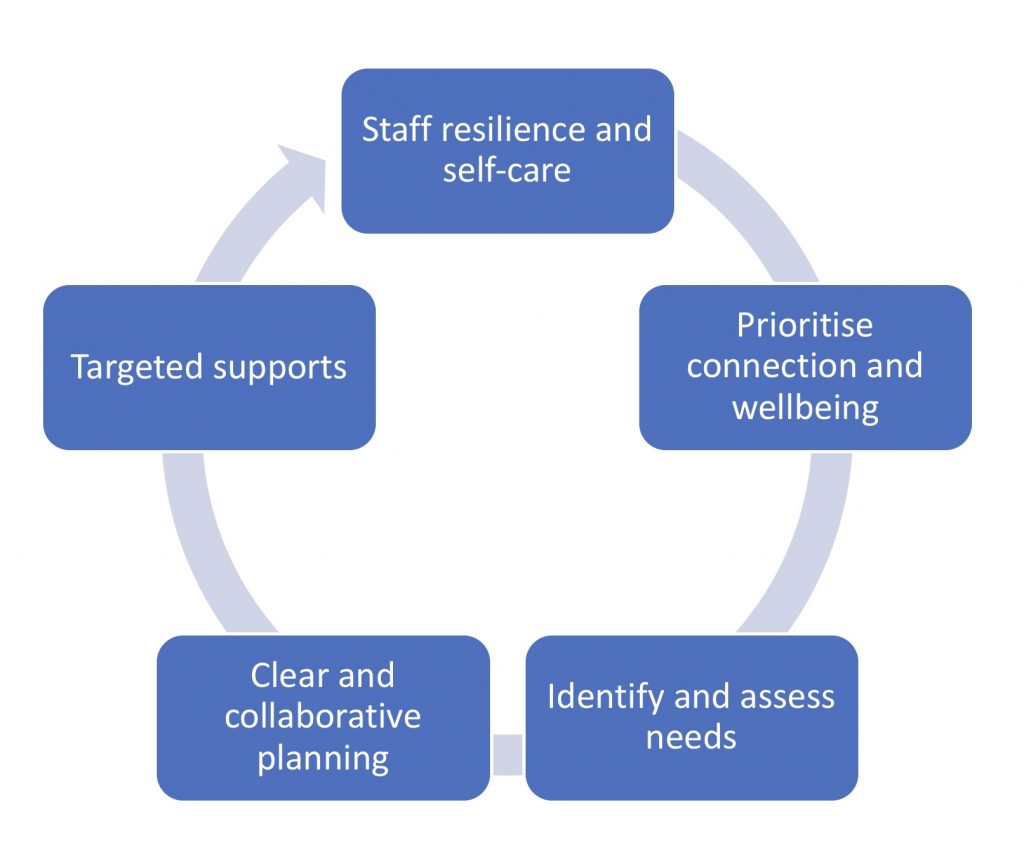

In the paper we outlined a key concepts framework for compassionate transitions (see Figure 1). I would argue that this has relevance for future educational practice and can be used as the basis to build a more prepared and resilient response. We were not prepared for the national lockdown in March 2020, and it is important that we learn from that experience to inform practice should such restrictions happen in the future.

In terms of application, key areas in the framework are not linear and should be used as appropriate to the context.

Figure 1: Key concepts of compassionate transition planning (based on a figure in the paper)

Staff resilience and self-care

It is important to acknowledge the importance of staff wellbeing in educational establishments. The pandemic has highlighted the importance for social connection at both personal and professional levels. As such, we should identify opportunities for staff working in educational establishment to connect with their colleagues. I would argue that if staff are well supported, they will be better able to self-regulate and thus support children and young people’s emotional needs.

Prioritise connection and wellbeing

The impact of a pandemic on people’s lives and their psychological wellbeing should be acknowledged in our thinking and practice. Educational staff and children and young people should be given space and opportunities to reflect on their experiences. We can draw on a range of established resources which help children understand and manage their emotional responses and those of the people around them e.g., compassionate and connected classroom and nurture as a whole school approach. The importance of connection links to the psychological need of relatedness as articulated in self-determination theory and well as an aspect of Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs.

Identify and Assess Needs

At a whole establishment level, it is important that there is ongoing self-evaluation and monitoring of pupils’ progress using available data. At the individual child level, in Scotland we have a National Practice Modelwhich provides a framework for undertaking further assessment and analysis of wellbeing indicators. It is also important to be aware that there may be hidden individual needs. For example, some children may be anxious, but this may not be communicated in school, either verbally or non-verbally.

Clear and collaborative planning

Communication and collaboration are important at all times but especially during a pandemic. School leaders have a key role to play in establishing, maintaining and evaluating policies in this area. Parents/carers have been affected during the pandemic (e.g. home schooling, job uncertainty, health concerns). It is important that they are viewed as equal partners in transition planning and implementation processes. Furthermore, the views of children and young people should be valued and actions taken by establishments to genuinely listen to their voices.

Targeted supports

Pupils with identified Additional Support Needs may be at greater risk during pandemics and require a more individualised approach to successfully manage any transitions during this time.

You can listen to Dr Hannah’s talk here.

Reflective questions

1. What have we done well to support transitions during the current pandemic?

2. How can these practices be used in potential future pandemics?

3. What have we done less well?

4. What could we do differently to improve our practice?

Acknowledgements: I would like to acknowledge my co-authors in the paper : Alison Crawford, Laura-Ann Currie, Jacqui Ward and Imogen Wooton

Dr Elizabeth F.S. Hannah is a Senior Lecturer in Educational Psychology in the School of Education and Social Work, University of Dundee. Her professional interests as an educational psychologist included educational transitions, the inclusion of children and young people with additional support needs, promoting children’s mental health and well-being, consulting with children, and action research. She is a member of a number of professional organisations and is registered as an educational psychologist with the Health and Care Professions Council.