Today on the #DundeeUniCulture blog we are sharing this fantastic review of a recent film adaptation of H.G. Wells’s classic novel The Invisible Man, written by University of Dundee’s very own Dr Keith Williams. Keith teaches Wells at Level 4 UG and on our Science Fiction Master’s – find out more about the course by visiting the website: https://www.dundee.ac.uk/postgraduate/science-fiction

Keith has also published a study of H.G. Wells, Science Fiction and Film back in 2007.

This review has been reproduced by kind permission of the H.G. Wells Newsletter.

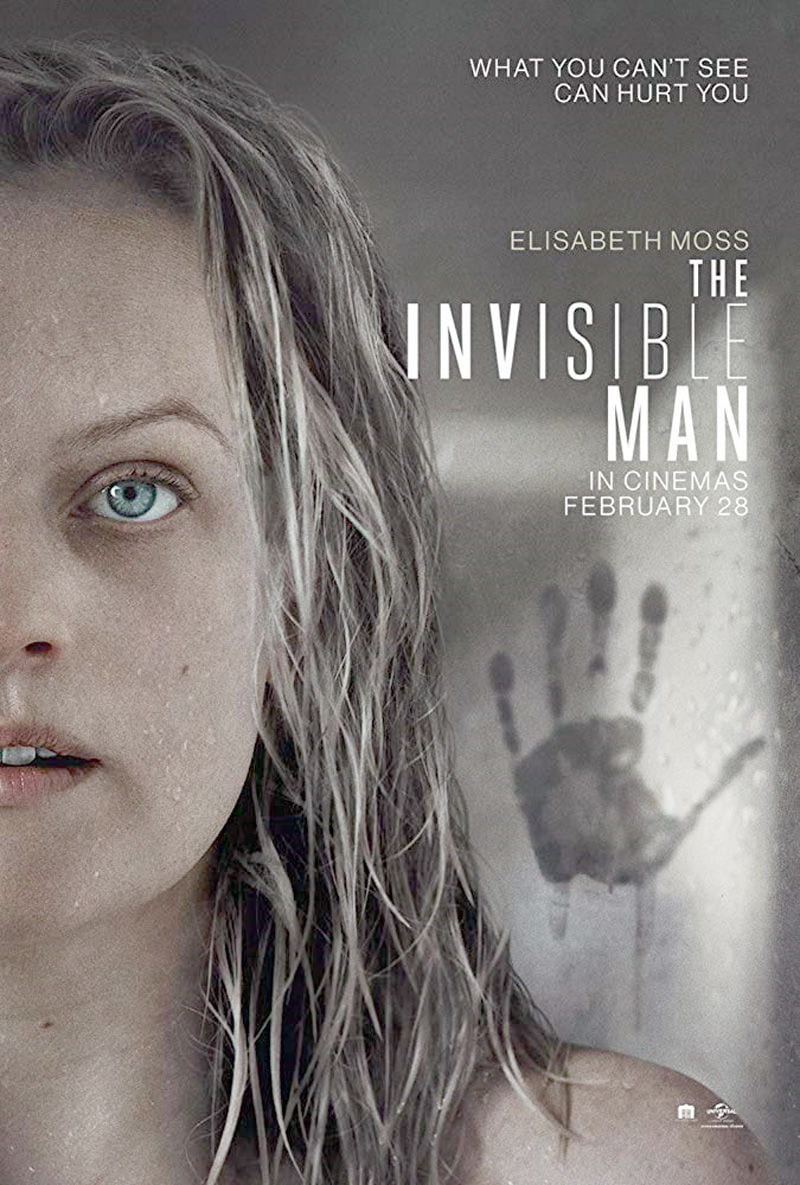

Review of ‘The Invisible Man’ (Dir: Leigh Whannell; Universal Pictures, 2020)

This is very much a Hollywood 2020 vision of the themes of H.G. Wells’s 1897 novel about the potential of new invisible forces to wreak havoc in late Victorian society by displacing human agency and creating absent presences through electromagnetism. Wells’s 1895 Story ‘The Remarkable Case of Davidson’s Eyes’ had suggested how modern media would expand the capabilities of televisual voyeurism and surveillance in the coming century. As its narrator comments, ‘It sets one dreaming of the oddest possibilities of intercommunication in the future, of spending an intercalary five minutes on the other side of the world, or being watched in our most secret operations by unsuspected eyes’. Novels such as The Invisible Man and When the Sleeper Wakes (1899) elaborated Wells’s insight.

It has become an instant cliché to call Leigh Whannell’s new film The Invisible Man for the ‘Me Too Generation’. Its accent is emphatically on the gendered noun, on the most toxic and controlling of dysfunctional masculinities in today’s techno-social system. Gone is all the macabre black humour of Wells’s novel which somewhat mitigates its escalating violence. This was remediated in early silent trick film versions, as well as most famously in James Whale’s 1933 adaptation, which first capitalised on the soundtrack to articulate Griffin’s invisible voice. Humour has been subsumed by a psychological, stalker horror with a feminist message, though arguably morally somewhat compromised by the brutal ending.

Oddly Whannell’s Invisible Man (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) has become virtually dumbstruck, vocal only in his visible state at the film’s beginning and end, apart from one gloating exclamation – ‘Surprise!’ – which ultimately prove his undoing. Whale used deliberate a-synchonisation between word and image to follow Wells’s prescient cues which align Griffin’s invisible eye with the moving, access-all-areas, point-of-view camera; his invisible voice, with sound recording and communications media which displace speaking subjects: Whale’s optical soundtrack itself, the telephone and above all radio broadcasting, the medium for transmitting disembodied electronic presences most favoured by the rising dictators of the 1930s. In Whannell’s film,

Griffin’s strategic silence is necessitated by his twisted project which replaces the proto-fascistic ‘Reign of Terror’ proposed by his Wellsian model. Wells gave only the briefest hint about the potentials of invisibility for indulging the perverse impulses of male fantasy, when Griffin watches young nannies wheeling their charges through the park. Whale gave his Griffin a first name and a heteronormative romantic backstory, to fit in with 1930s Hollywood’s box-office formula and show that, pre-transformation, he is just an ordinary ‘Jack’. But this is exactly where Whannell’s re-imagining is most radical in its departure from both Wells’s novel and Whales’s hugely influential film. Not only is his central character completely new, but she is also Griffin’s antagonist. Cecilia (Elisabeth Moss, cast for her pre-associated role in Margaret Atwood’s gender dystopia, The Handmaid’s Tale) escapes from her abusive partner to a safe house only to learn that he has unexpectedly committed suicide. However, she quickly finds herself being haunted by an uncanny posthumous presence, which recreates Wells’s scientisation of traditional ghostliness in the text.

Griffin seeks to ‘Gaslight’ his ex (Whannell drawing on Thorold Dickinson’s 1940 film inspiring the colloquial term for the abusive process), so that she begins to doubt the evidence of her senses and others doubt her sanity. This appears to succeed as Griffin’s psychopathic atrocities are pinned on her. After all what could appear more dangerously hysterical than a knife-wielding woman claiming persecution by a presence no one can see? However, Cecilia, unlike Griffin’s landlady Mrs Hall and the other superstitious villagers of Wells’s Iping, remains rational enough to think the apparently impossible: her ex-partner has both faked his own suicide and devised a way of rendering himself invisible.

Despite silencing Griffin’s invisible voice, Whannell nonetheless extends his profound connection with contemporary media. His Griffin, now named ‘Adrian’, is not Wells’s alienated albino ‘freak’ struggling to overcome the prejudices of a normative community and his own obscure poverty, but a Silicon Valley genius. He is a recognised world expert on optics making billions from patents and sitting atop the corporate patriarchy. As if to simultaneously emphasise that ‘Alpha Male’ success is predicated on deep insecurity, Adrian lives in a virtually transparent hilltop mansion, surrounded by plate glass windows and a security camera system covering every space in and around his glittering, designer compound. The paradoxical role of clothing, both concealing Griffin’s invisible identify and the physical vulnerability of his nakedness, has also been fundamentally changed. Gone is Wells’s spooky slapstick of empty shirts running around and gags like self-pedalling bikes. Instead Adrian wears a patent body suit which acts as a ‘cloaking’ device, alluding to actual scientific and military experiments with such technology allegedly close to realisation. Unlike the novel, he is no longer a body rendered transparent by mysterious X-ray-like electromagnetic radiation (on the same spectrum of forces that make modern media possible). His artificial second-skin is tessellated with tiny cameras, in a kind of updating of the myth of Argus, the panoptic giant with a thousand eyes. But Adrian’s lenses are not so much to see, as to render him unseeable by chameleonically reflecting back his surroundings.

Joseph Conrad dubbed Wells the ‘Realist of the fantastic’ after relishing The Invisible Man, an accolade also applicable to cinema, then only a few years old, as the modern medium containing the greatest potential for visualising the familiar and the impossible on a virtually equal plane of ultra-mimetic or ‘simulacral’ realism. The VFX in Whannell’s film live up to this tradition, especially in the subtle ‘tells’ which give Adrian away to the fine tuning of Cecilia’s other senses. She realises her solitude is broken by sounds of disembodied breathing, by barely audible footsteps or indentations on chairs. Instinct alerts her to another living body in her bedroom. Though she scours the whole house for intruders and finds no one, the audience can still see someone’s else’s breath vaporising in the cold air behind her outside the front door.

The Invisible Man infiltrates Cecilia’s most intimate private spaces and rifles through her things. In the film’s creepiest moment, he pulls the duvet off the bed she shares with the teenage daughter of her protector. Snapping them both with a flashing i-phone, he carries out the ultimate act of ‘revenge porn’, possessing the sleeping women’s images against their will. What could be more indicative of ‘being watched in our most secret operations by unsuspected eyes’ and the chilling feasibility that in our digital age this may already be the case? The film taps into an obvious, partly paranoid, but no less imperative topical theme in a world which the thought experiments of Wells and other contemporary scientific romancers helped dream into being. Murky dalliances between twenty-first century governments and global tech corporations have resulted in the phenomenon of ‘surveillance capitalism’, in Shoshana Zuboff’s phrase. Fear of the violation of privacy is now part of everyday reality, whether of our physical presences or of our most personal data. This threatens to make the world – in another of Wells’s phrases from ‘The Stolen Body’ (1898) – a ‘great glass hive’, significantly repeated by Wells’s proto-Big Brother, Ostrog, who operates a city-wide CCTV system in his corporate dystopia, When the Sleeper Wakes. It is a nightmare of total transparency, that everything about our lives might be insecure and visible to unwarranted scrutiny and intrusion. Today’s proliferation of phone hacking, secret cameras (Cecilia tipp-exes out her laptop’s webcam for fear it has been hijacked), GPS tracking through mobile devices, big data harvesting by internet AI algorithms (Wells’s imagined ‘World Brain’ has come to pass), facial recognition technology and tagging from social media postings could spell the final end of privacy and anonymity. Adrian also operates a counterpart, invisible on-line presence as digital harasser and identify thief by hacking Cecilia’s email account to impersonate her and send abusive messages to her sister, prising them apart. He is both technological voyeur and data gatherer, who takes full advantage of the ever more enhanced means of stalking afforded by digital media. Thus Adrian is able to contaminate the very concept of intimacy itself with a chilling new meaning as he tries to persuade Cecilia of the merits of reviving their relationship: ‘I am the person who knows you best.’

Although men may also fall victims to such violations, women are more often targeted and understandably more vulnerable. Symbolically, it is even suggested Cecilia’s unwanted pregnancy may be the result of invisible rape while drugged and unconscious. In keeping with Wells’s persistent warnings about the inherent risks of products of science outpacing collective human ethics and wisdom, Adrian’s invention is both literally and symbolically disruptive, operating in advance of and outside any kind of legal consciousness or constraint. It is noticeable that Cecilia’s host, a burly, but sympathetic policeman (Aldis Hodge), can neither understand nor deal with the force of Griffin’s invasive criminality and is only brought up to speed by experiencing its impact when it is almost too late. Ironically, the only other prominent legal professional in the film is Adrian’s brother. His ‘executor’, Tom is finally unmasked as his co-conspirator in his campaign to drive Cecilia back into his control.

Much of the latter half of the film trades topical critique and psychological tension for blood-spattered action thrills. The tables are only finally turned when Cecilia, after escaping a maximum security psychiatric hospital amid mass slaughter caused by Adrian, takes the law into her own hands with equal goriness. However, there is also something quite powerful in how she appropriates Adrian’s technology, which arguably channels an alternative imaginative tradition of female invisibility. This goes back to C.H. Hinton’s pre-Wellsian Stella (1895), in which it is a social experiment to deconstruct the performance of Victorian femininity; to film spin offs from Whale, such as The Invisible Woman (1940) which replicates Griffin’s electromagnetic process to take semi-comic revenge on men who have exploited its protagonist. After failing to cajole Adrian into confessing his crimes (by wearing a wire relaying their conversation to her policeman host invisible in a car outside), Cecilia restages Adrian’s suicide, recording his apparent actions on his own CCTV system, while her likely presence in the room manipulating the knife is unregistered. This is both neatly meta-cinematic and symbolic of how the gendered dynamics of digital media might be challenged. For that reason alone, Whannell’s re-imagining of The Invisible Man’s themes is more than worth watching and testifies to their longevity.

Dr. Keith Williams University of Dundee, 11/5/20

Horton, Adrian, 27/02/2020, “Hidden figure: how The Invisible Man preys on real-world female fears”, The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/feb/27/the-invisible-man-movie-real-fears-women

Gleiberman, Owen, 01/03/2020, “The Success of The Invisible Man Reveals the Fallacy of ‘Get Woke, Go Broke’, Variety: https://variety.com/2020/film/news/the-invisible-man-reveals-the-fallacy-of-get-woke-go-broke-elisabeth-moss-1203520048/