Kelsey Williams from the University of Stirling explores the treasures he found in the University of Dundee Archives’ rare book collections.

When printed books first arrived on the scene in fifteenth-century Europe they didn’t come into a vacuum. Far from it. While printing dramatically multiplied the number of texts available to Europeans, the continent was already filled with hundreds of thousands of manuscripts, lavish and cheap(ish), sacred and secular, large and small. Over the following centuries some of these manuscripts were lovingly preserved but far more were discarded as irrelevant, heretical or simply unnecessary.

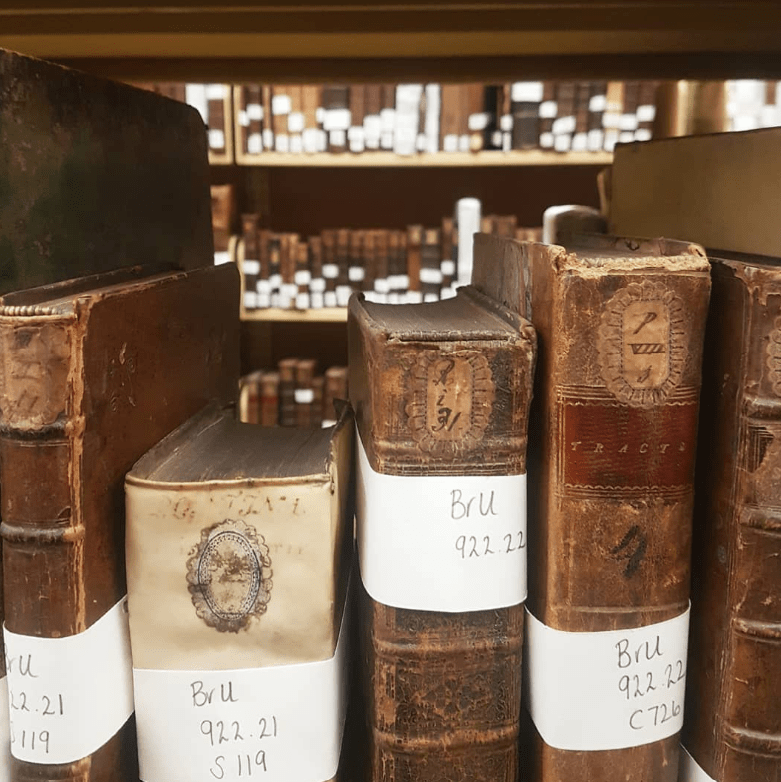

Early modern Europeans, however, were great recyclers and one of the many ways in which manuscripts could be recycled was as binding material for new books. These snipped up fragments of manuscript – lumped in the general category of “binding waste” – are hidden inside the spine or underneath the endpapers of many an early modern book, but sometimes either binding technique or subsequent damage reveal the contents of these precious time capsules. Recently I was working in the Brechin Collection at Dundee, hunting for these fragments, and was delighted to find no fewer than twenty volumes, printed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which contained more or less substantial pieces of manuscripts from before the age of print.

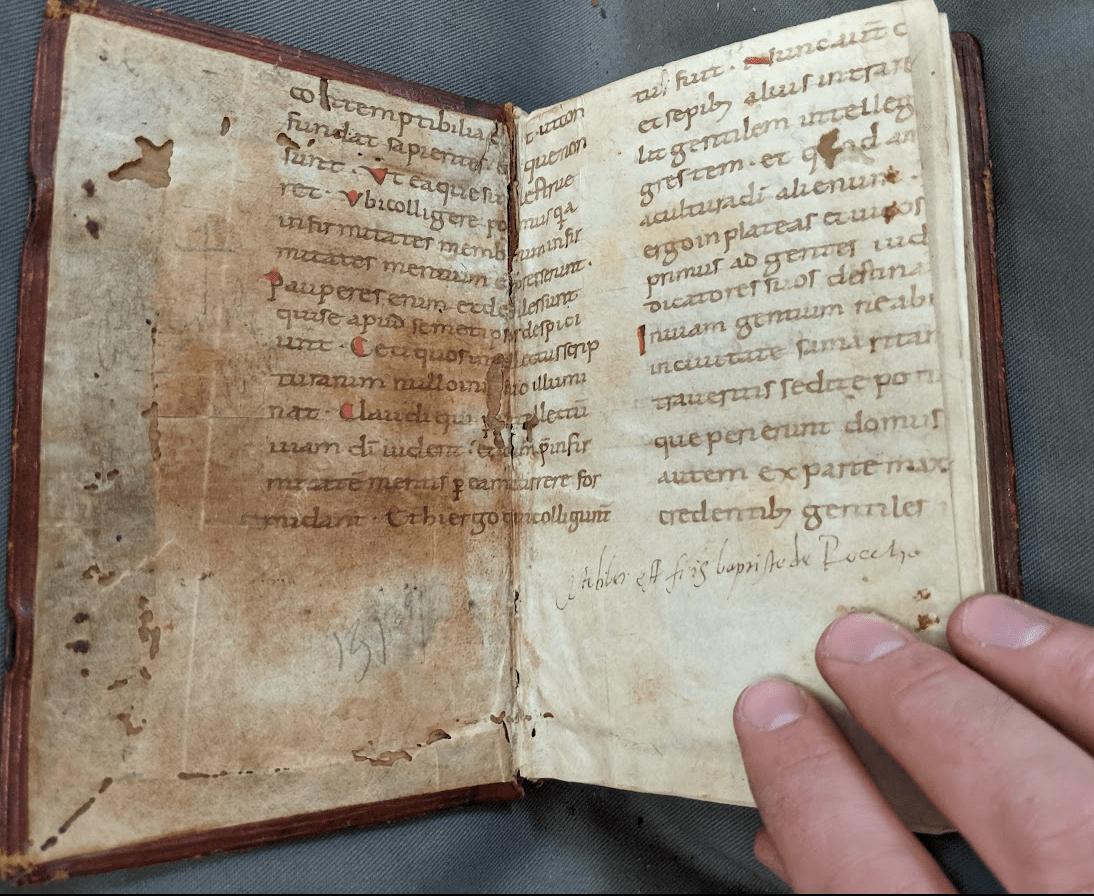

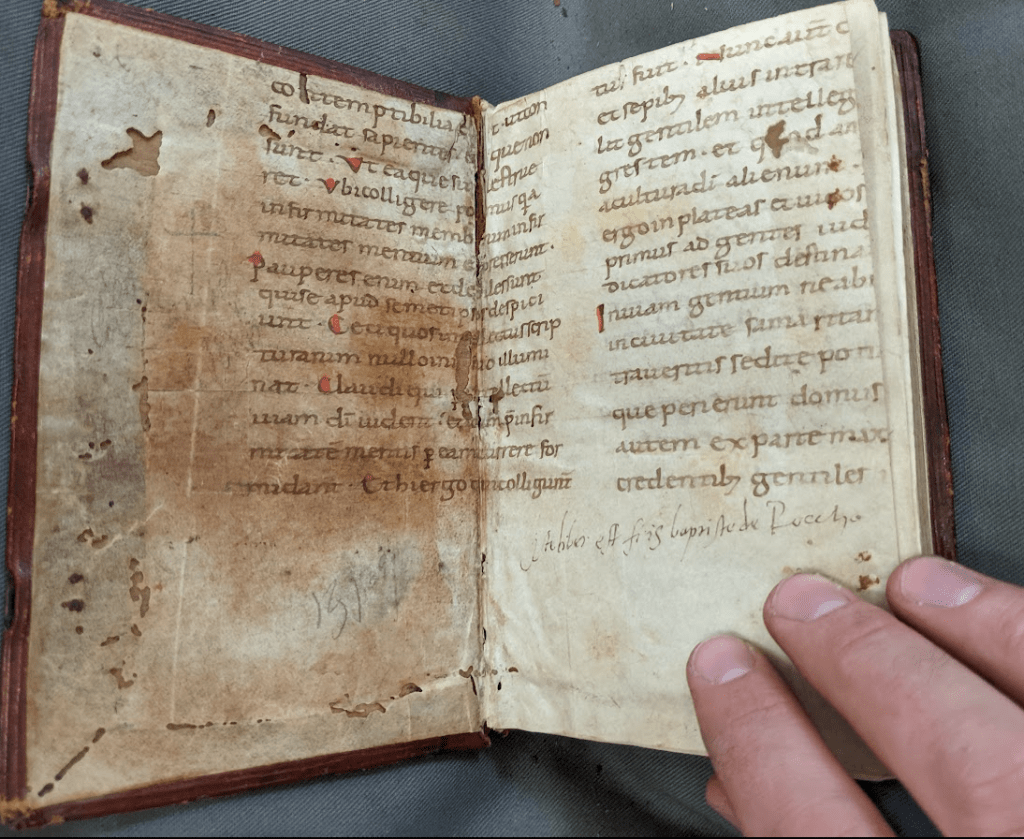

This small but wonderful collection demonstrates the varied ways in which manuscripts could be repurposed. Spectacular examples include a 1625 Frankfurt edition of Edmond Richer’s Midwife of Souls bound in two leaves from a thirteenth-century Bible and a copy of Torquemada’s Exposition of the Psalter which has endleaves made out of part of a twelfth-century copy of the Homilies of the Benedictine Haimo of Auxerre.

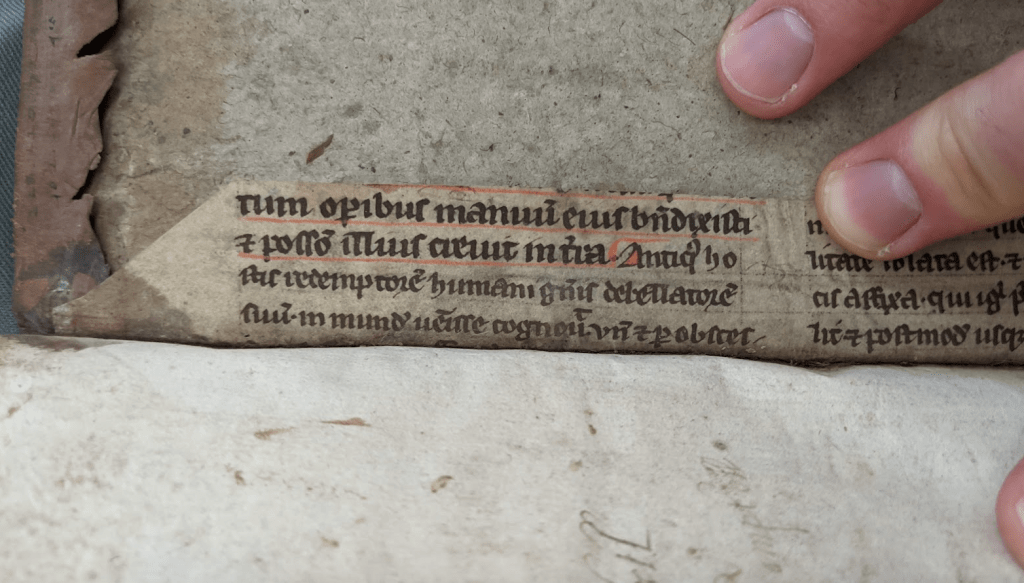

Most of the time, however, only small fragments are visible, as in Victorinus Bythner’s 1653 Lyra prophetica which has had its spine strengthened with scraps from Pope Gregory the Great’s Exposition on Job.

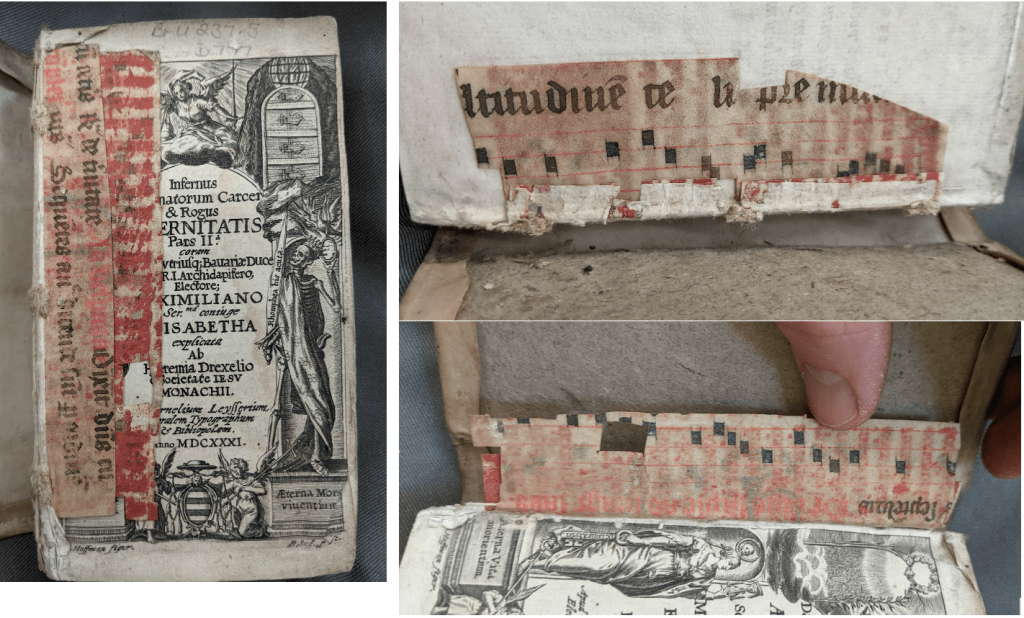

My favourite, however, is one of the many popular devotional works of the Jesuit Jeremias Drexel which shows not one but two layers of recycling. What was once a large and beautiful manuscript of liturgical music has first been cut into a frisket for a printing press and subsequently reused for strengthening the book’s spine. In its final form it displaces not only the beauty of its original form but a thick layer of red ink leftover from its use in the printing process.

Although small and fragmentary, these scattered pieces of parchment are precious witnesses to the culture of the middle ages. As the science of “fragmentology” continues to develop, scholars – myself included – are becoming increasingly interested in what these very material relics of a vanished age can tell us about how our ancestors lived, read, and used their books.

Kelsey Jackson Williams

University of Stirling