As human beings we are all dependent on the land and the resources it provides. Yet we are increasingly becoming disconnected from the natural world around us and our overexploitation of the land is causing an environmental crisis. The latest exhibition in the Lamb Gallery at the University of Dundee looks at ways in which we have explored, represented and exploited the land and how artists in Scotland have responded to these themes over the years. The exhibition, entitled Un-Earthed draws on a wide range of artworks, artefacts and specimens from the University’s Museum Collections.

Here are a few of the highlights on display:

The Rhynie Chert beds near the village of Rhynie in Aberdeenshire are important and exceptionally well-preserved fossil sites that reveal much about the evolution of early plant life from the Devonian period, around 400 million years ago! At this time, the earth’s geography was a big mass of land in the Southern Hemisphere with smaller continents in the equatorial region. What we now know as Europe resided near the equator. The Rhynie Chert beds were in a tropical to subtropical climate and consisted mostly of flatlands and short-lived shallow pools of fresh water, perfect for plants to grow. This example includes fossilised lycopods known as clubmosses, which once grew large and tree-like into huge forests that dominated the landscape.

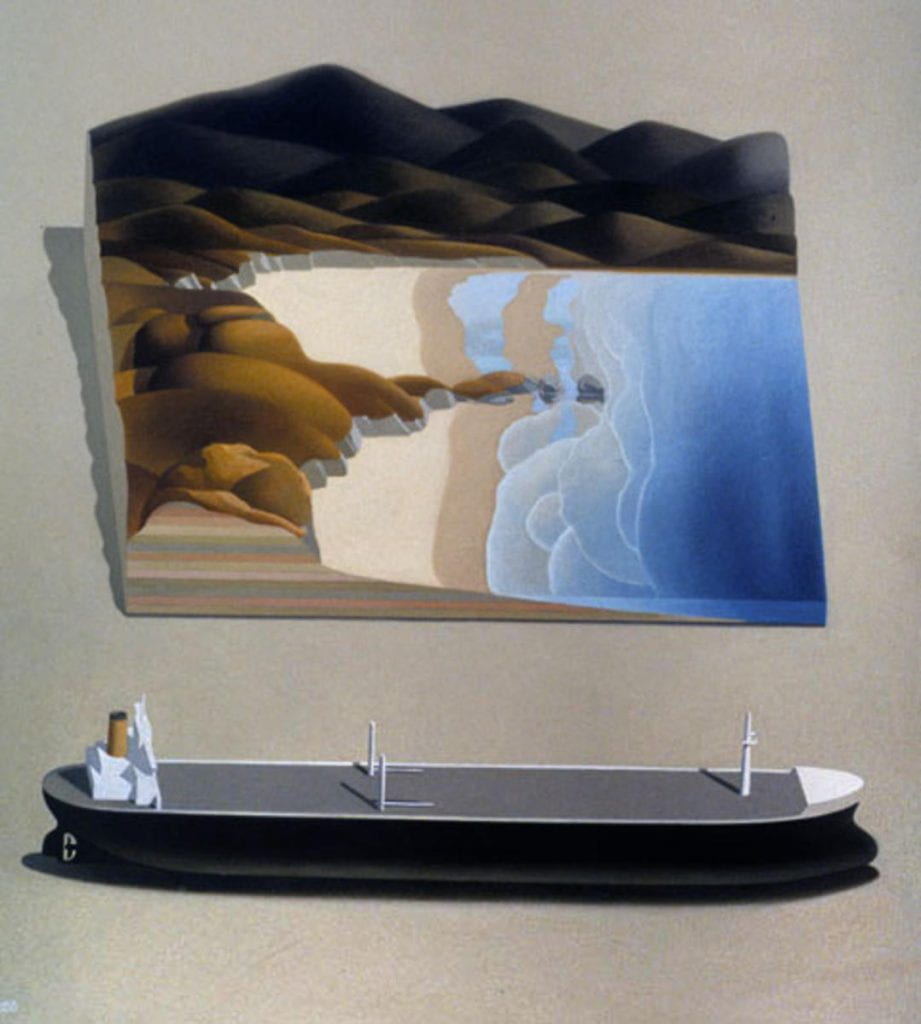

Professor Alan Robb was Head of Fine Art at Duncan of Jordanstone College from 1983-2003 and then an Emeritus Professor until his death in 2020. He had a huge influence on art education in Scotland, as well as on the careers of many successful alumni. This is one of four paintings kindly gifted to us by his wife Cynthia after his death.

Empty Beach with Tanker comes from a series of works by Robb relating to the Braer oil tanker which ran aground off Shetland during a storm. The tanker hit rocks in Quendale Bay, just west of Sumburgh Head, on the south tip of Shetland’s mainland, just before midday on 5 January 1993. The captain and crew were airlifted to safety by helicopter but there was a major oil spill releasing almost 85,000 tonnes of crude oil into the sea.

According to WWF Scotland, at least 1,500 birds died and up to a quarter of the local grey seal population was affected. However, the situation could have been a lot worse as the strong winds nearly a week later (the most intense extratropical cyclone on record for the northern Atlantic Ocean) blew most of the oil away from the shore.

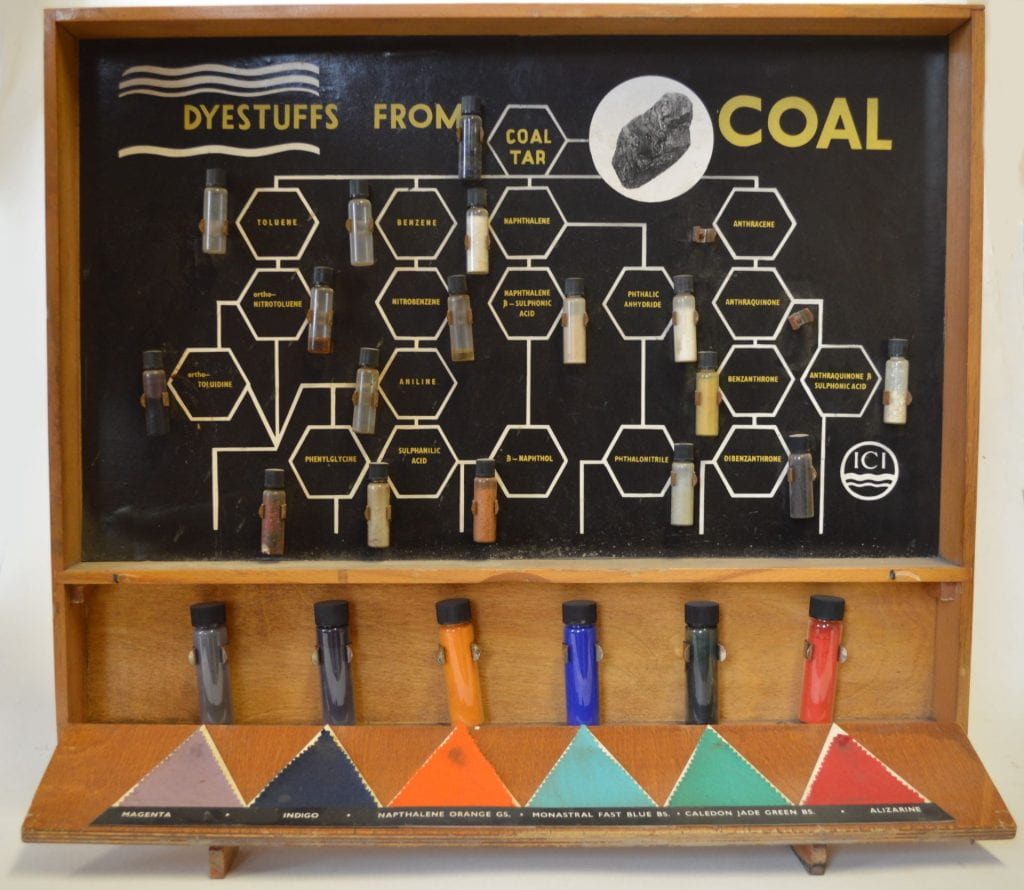

In 1856 the first synthetic dye was produced from aniline, an oil derived from coal tar. The dye, mauveine, was used to create the colour mauve which became highly fashionable at the end of the 1850s. The contagious nature of the colour’s popularity was mocked in Punch magazine as the “mauve measles”. However, the dye (like the fashion) proved not to be lasting and by 1870, demand succumbed to newer synthetic colours in the dye industry that Mauvine had launched.

This display created by Imperial Chemical Industries (better known as ICI) shows some of the most popular dyes they had available in the 1950s and 60s. Many colourful dyes had been developed from coal tar chemicals around the turn of the century. However, one thing that was still missing was a good green dye which was both bright and long lasting. In 1921, Arthur Davis, Robert Fraser Thomson and John Thomas of Scottish Dyes Ltd at Grangemouth (which would later merge with ICI) developed ‘Caledon Jade green’. This bright and highly coloured dye for cotton and rayon was especially resistant to laundering as well as bright sunlight. The hue became an immediate success and remined in production until the 1970s.

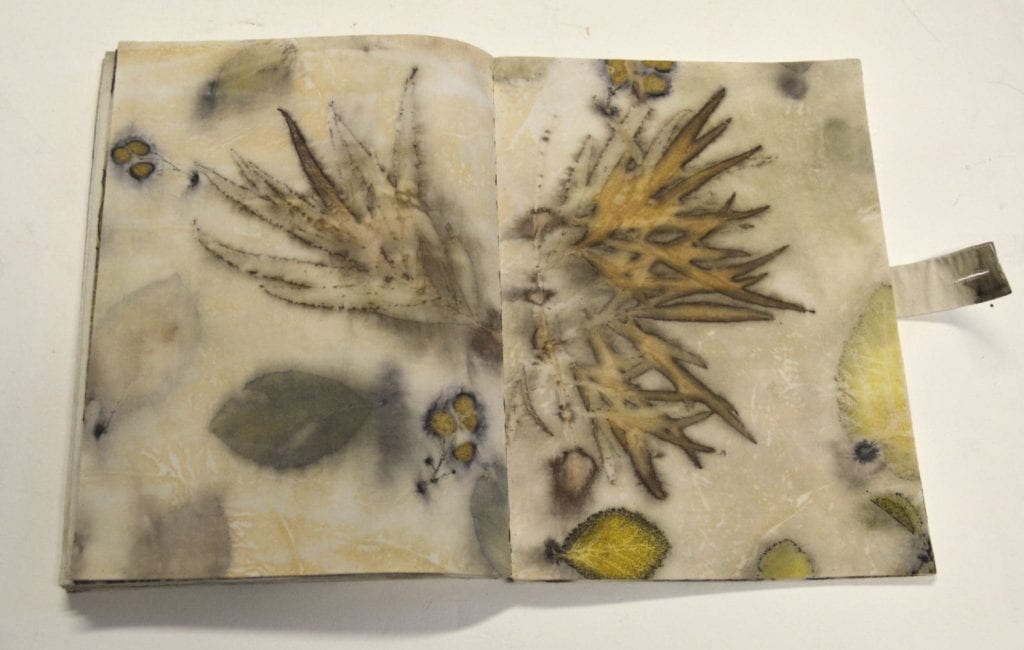

In recent years, thanks to a growing recognition of the importance of using sustainable and biodegradable materials, dyes derived from natural sources have once again gained interest. Contrasting the synthetic dyes derived from coal, this book was created while the artist was studying on the MFA Art Science & Visual Thinking course at DJCAD. Brown studied the processes of extracting dyes from botanical matter and made this book using botanical contact printing, also known as eco-printing.

The process of botanical contact printing involves bundling together roots, stems, leaves, flowers, fruits and other organic materials with layers of fabric and then boiling or steaming them to transfer the colours and patterns onto fabric. The shade of the colour each plant produces will vary according to various factors such as the time of the year the plant was picked, how it was grown and the soil conditions. With so many variables the outcome is always a surprise. Brown describes this method as “capricious, gracious, unpredictable, consistent with nature, of which we are part”.

You can discover and listen to more object stories from the exhibition though our free digital guide on Bloomberg Connects.

Un-Earthed will be on show until 27 April, and is open from Mon-Fri 9.30am-7pm and Sat 11am-4pm. The Tower Building may close earlier on some weekdays so we advise arriving no later than 5pm. Find out more at Un-Earthed | University of Dundee, UK