Introduction

In this short resource, we’ll explore one possible approach for documenting and synthesising a large body of research

When you’re conducting research, it’s important to be able to both record that research and to synthesise your findings (to identify links between different sources). There are many different ways in which you can keep track of your activity, ranging from old fashioned pen and paper to referencing management software.

Using a spreadsheet to record and synthesise research

One quite useful way to get a broad overview of your literature and to begin to synthesise evidence around similar themes is to use a very simple spreadsheet.

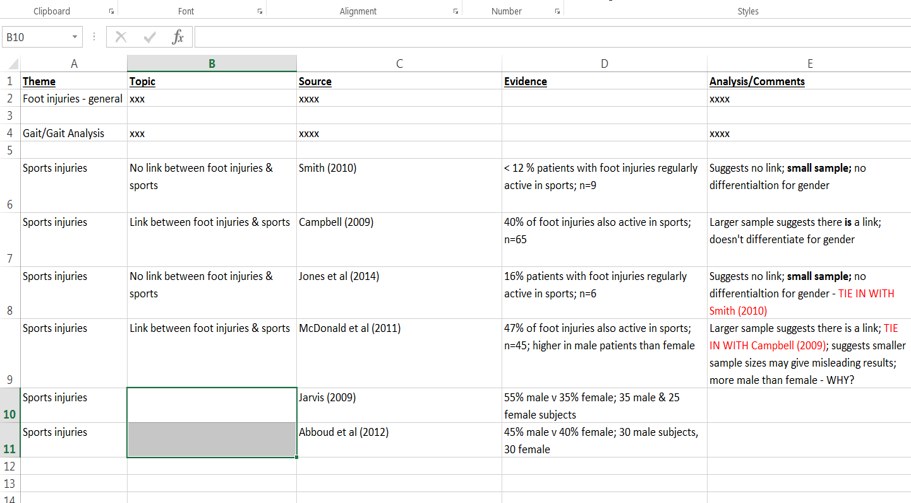

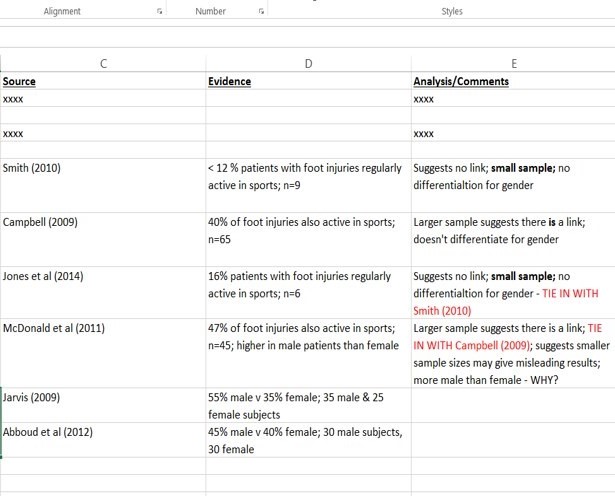

In the example below, we’ve started to gather some ideas from our research into sports injury. The categories along the top allow us to start to think about synthesising and grouping evidence according to themes, dates, or whichever category is most appropriate.

These categories can be adapted in all sorts of ways to accommodate your particular needs and the level of detail you wish to capture on the spreadsheet.

As well as being useful in terms of recording and organising your research, this approach can help when it comes to writing up the research too – we’ll explore that next.

Writing up the research

As we mentioned, you can adapt the heading on your spreadsheet to suit your needs. Here they’ve been set up to optimise a simple TEA model for writing paragraphs. We explore the TEA model in detail in our resource on Planning and Structuring Your Writing.

First of all we have the broad theme (column A), in this case Sports Injuries. This might relate to the an essay or chapter subheading, or even to the theme of the essay or chapter itself in a longer piece.

In the next column, we have the topics thrown up by the research. In this example, we have two – i) studies which show no link between foot injuries and participation in sports, and ii) studies which do suggest a link. Can you see how this format allows us to easily pull together similar topics/findings? These can form the basis of our topic sentences.

We have columns which list the source and detail the evidence from that source – perfect for our evidence element of TEA. And finally, we have recorded our own analysis and comments, which will form the basis of our critical commentary (the analysis in TEA). Again, note how easy the format makes it to link different studies and synthesise them in our writing.

Let’s take a look at how we can use this information to begin planning our paragraphs…

Paragraph 1

Topic…

A number of studies have been conducted into the links between foot injuries and sports participation.

Evidence…

Smith (2010) found that fewer than 12% of patients presenting with foot injuries also participated regularly in sports activities, in a study of 9 patients. Jones et al. (2014) identified a similar figure of 16% in their study of 6 patients.

Analysis…

The low rates suggest that there is little link between participation in sports and the occurrence of foot injuries. It should be noted, however, that these studies both had small sample sizes and made no distinction between genders.

Paragraph 2

Topic…

Indeed, larger-scale studies have found very different results.

Evidence…

Campbell (2009) found that 40% of patients presenting with foot injuries also participated regularly in sports, in a study of 65 patients. Similarly, McDonald et al. (2011) identified a rate of 47% in their study of 45 patients. They also identified a significantly higher correlation between sporting activity and foot injuries in male patients compared to female patients.

Analysis…

These studies cast some doubt on the earlier positive findings. It is notable that both studies draw on much larger sample sizes than those of Smith (2010) and Jones et al. (2014), perhaps suggesting that results in the latter were skewed by their small sample size. The findings of McDonald et al. that gender may play a role are also potentially significant.

Putting it all together…

A number of studies have been conducted into the links between foot injuries and sports participation. Smith (2010) found that fewer than 12% of patients presenting with foot injuries also participated regularly in sports activities, in a study of 9 patients. Jones et al. (2014) identified a similar figure of 16% in their study of 6 patients. The low rates suggest that there is little link between participation in sports and the occurrence of foot injuries. It should be noted, however, that these studies both had small sample sizes and made no distinction between genders.

Indeed, larger-scale studies have found very different results. Campbell (2009) found that 40% of patients presenting with foot injuries also participated regularly in sports, in a study of 65 patients. Similarly, McDonald et al. (2011) identified a rate of 47% in their study of 45 patients. They also identified a significantly higher correlation between sporting activity and foot injuries in male patients compared to female patients. These studies cast some doubt on the earlier positive findings. It is notable that both studies draw on much larger sample sizes than those of Smith (2010) and Jones et al. (2014), perhaps suggesting that results in the latter were skewed by their small sample size. The findings of McDonald et al. that gender may play a role are also potentially significant.

Creating flow

Notice how the paragraphs ‘speak’ back and forward to each other. For example, the final sentence of the first paragraph (small sample size) sets up the next paragraph (different results from lager samples), and the analysis part of the second paragraph refers back to the evidence from the previous paragraph. The final point in the second paragraph also suggests our next paragraph might be about studies that looked specifically at gender.

This is what gives your writing ‘flow’ but it’s hard to achieve this kind of structural coherence without planning things out first.

Summing Up

Seeing the bigger picture and synthesising your research is one of the keys to moving away from a descriptive approach to the evidence and instead taking a more critical and nuanced approach to that evidence and the role it plays in your writing.

There are many ways you can do this – perhaps you have some other tools in mind which will allow you to achieve this important task. But if not, the spreadsheet approach might be worth exploring.