Introduction

At university – and particularly at postgraduate level – a lot of emphasis is placed on ‘being critical’ or ‘taking a critical approach’ but it can be difficult to know how you go about achieving that, particularly at first.

On this page we’ll explore what it actually means, look at ways of being more critical, and begin to explore what criticality might look like in the context of your subject(s).

What does ‘being critical’ mean?

In some ways the concept of criticality defies easy definition. A critical approach should run across much of what you do as a master’s student – from how you organise your time to how you engage with classes and study, and how you tackle assignments. For that reason, a simple definition can be misleading, or insufficiently thorough.

A useful way of trying to define what ‘being critical’ means at master’s level is to turn to the facets of taught postgraduate (TPG) study identified in the QAA Mastersness Toolkit. Criticality isn’t a facet in its own right – instead it permeates several of the areas identified in the toolkit.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it features strongly in the ‘Research and Enquiry’ facet, which is defined as ‘[d]eveloping critical research and enquiry skills and attributes’ (QAA, 2014). Likewise, critical thinking is also mentioned explicitly in the definition of the ‘Depth’ facet. But it’s also there implicitly in many of the other facets, such as ‘Abstraction’ (‘Extracting knowledge or meaning from sources and then using these to construct new knowledge or meanings’), ‘Complexity’ (‘Recognising and dealing with complexity of knowledge’) and ‘Unpredictability’ (‘recognising that real world problems are messy and complex, being creative with the use of knowledge and experience to solve problems’).

Key concepts

Two particularly important concepts in regard to critical thinking are analysis and evaluation. This short video provides a nice introduction to the role they play, and to the art of critical thinking in general.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

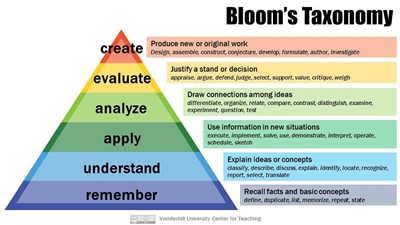

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a useful framework to help us understand where criticality fits in terms of our learning at master’s level. Bloom identifies a hierarchy of learning, with lower order skills such as memorising and understanding and higher order skills such as analysis, and evaluation.

There will usually be some lower-order description and demonstration of understanding in the classes you take, the research you do and the assignments you write – the problem comes when your work never gets beyond that descriptive level.

How do you take a critical approach in your subject?

So far, we’ve looked at criticality in a fairly broad sense. We’ve seen how crucial it is to many areas of master’s study, but how might you start to apply this important concept to your own field of study?

Whilst it’s impossible to get too far into specifics of different subject areas, we can pick up some very useful ideas from the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF). In their descriptors for Level 11 (the level to which master’s courses are mapped), there are numerous references to criticality and critical thinking:

- ‘A critical understanding of the principal theories, concepts and principles.’

- ‘A critical understanding of a range of specialised theories, concepts and principles.’

- ‘Extensive, detailed and critical knowledge and understanding in one or more specialisms, much of which is at, or informed by, developments at the forefront.‘

- ‘A critical awareness of current issues in a subject/discipline/sector and one or more specialisms.’

- ‘Apply critical analysis, evaluation and synthesis to forefront issues, or issues that are informed by forefront developments in the subject/discipline/sector.’

- ‘Critically review, consolidate and extend knowledge, skills, practices and thinking in a subject/discipline/sector.’

- ‘Practice in ways which draw on critical reflection on own and others’ roles and responsibilities.’

In terms of learning then, there is an expectation that the research you conduct should be critical both in breadth and depth – you should have a broad critical understanding of the key theories, ideas, names and arguments in the field as a whole, and a deeper critical engagement with specific areas that you may be working on, and especially with the current debates in those areas.

More than that though, the final two points emphasise a critical approach to the very practices of your discipline – to not just what you study, but how you study.

Practical ways to develop your criticality

- Reflect upon a recent piece of work you’ve done, or something you’re working on just now. Where would you place that work on Bloom’s Taxonomy? Are you reaching the higher order skills – like analysis and evaluation – or does your work still tend to exhibit mostly lower order characteristics like description and demonstration of understanding?

- Read Kipling’s Six Honest Serving Men and think about how you might use these prompts – What? Why? When? How? Where? Who? to help you take a more critical approach to your work.

- Brainstorm the ways you could take a more critical approach in your classes, research, assignments and general master’s study. You might wish to use the QAA Mastersness Toolkit and/or the SCQF Level 11 Descriptors to help give you some ideas.

Summing Up

When you begin to study a subject, and particularly when you take the kind of critical approach we have been discussing in this resource, you become more than just a student – you become an active participant in that discipline, you become part of the conversation.

Taking a critical approach allows you to start reflecting upon and defining your professional identity. You can begin to identify arguments or ideas you are drawn towards, and those you find less convincing. You begin to define and communicate where your beliefs and values lie within the field. In short, you begin to take up a particular position within the discipline area.

This is not possible without a critical approach. If you merely seek to understand everything about your subject area, you will be knowledgeable but that knowledge will not get you terribly far. When you start to question beliefs, when you seek and interrogate evidence, when you synthesise and evaluate, then you become much more than a bystander – you become an active participant in your subject area.