PhD student, Sylvia Valentine, shares some of her research on an outbreak of smallpox in Dundee in the early 20th century.

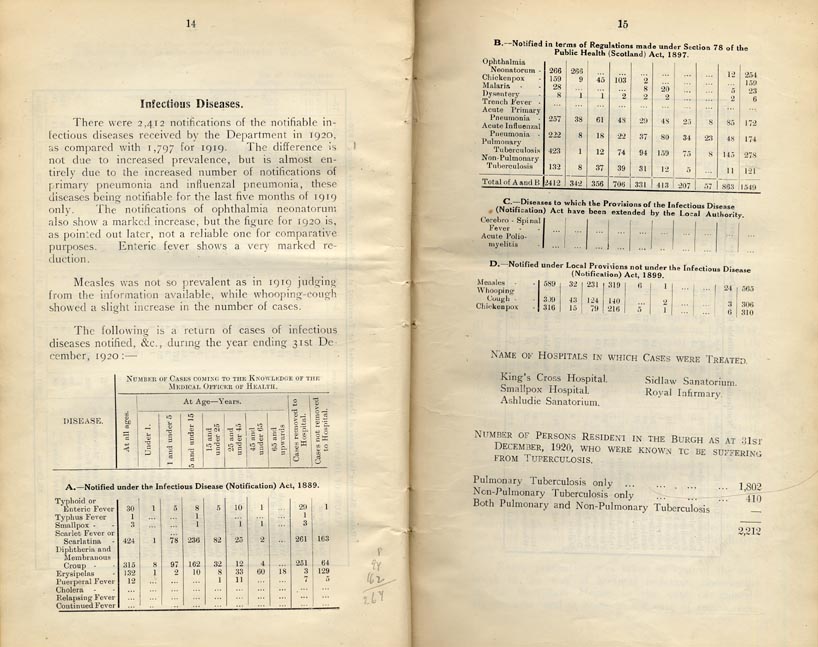

The University of Dundee archives hold a collection of records for the Dundee Kings Cross Smallpox Hospital.[i] Amongst the individual patient records are seven relating to British seamen who had been crewing the steam ship Pindari when it arrived in Dundee in January 1906. Using contemporary newspaper records it has been possible to piece together the story of the smallpox scare and to see how the medical authorities used the available public health measures to minimise the risk of a smallpox epidemic at a time when the city, and most of Scotland, had been relatively free of infection for some time. The nature of the newspaper accounts reflects the prevailing attitudes and language of the period.

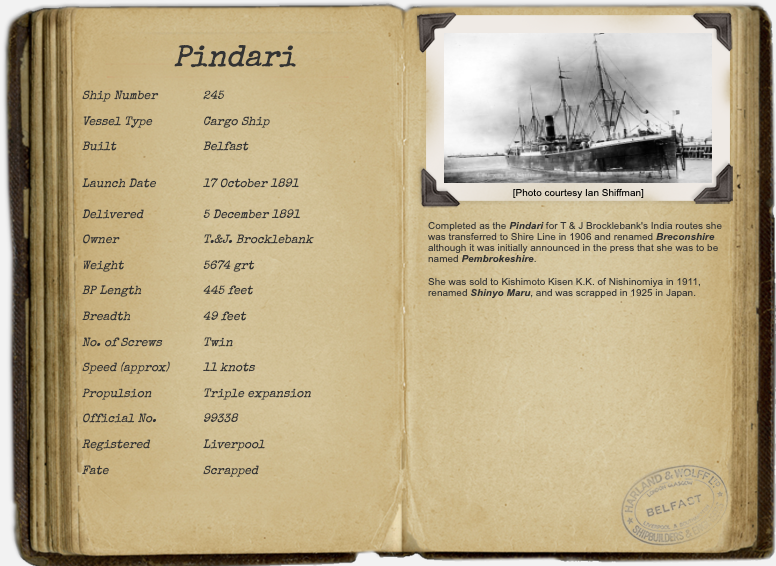

The Pindari was owned by T & J Brocklebank Ltd of Liverpool and was a ship of their so-called Dundee jute fleet.

Bringing a cargo of jute from Calcutta (Kolkata) to Dundee, it dropped anchor in the Tay on 29 January flying a yellow quarantine flag. The Pindari left Calcutta on 27 December 1905, sailing via the Suez Canal. It left Port Said in January before continuing its journey to Dundee.[ii] Crewed by a small contingent of British officers, the remaining crew being made up of Lascars; sailors from the Indian subcontinent.[iii] The voyage of the Pindari from Calcutta to Dundee can be tracked from the Shipping News in the local press and Lloyds List.

The Pindari was carrying an additional crew on this voyage who were on their way to Belfast, where they were to crew a new ship which was joining the Brocklebank fleet. Fortunately for all on board, owing to the size of the crew, the ship’s complement included a doctor, which was not normal practice. Usually the Chief Officer would usually treat any sick crew, using the advice from a Board of Trade handbook.[iv] Shortly after leaving Calcutta it was confirmed that three of the Lascar sailors were suffering from smallpox.

The infected Lascar crew were taken to hospital in Suez but this failed to contain the outbreak, which subsequently also affected the British officers. By the time the ship dropped anchor in the Tay, ten of the crew had contracted smallpox, including seven of the British crew. One of the Indian crew died later in the day and is buried in the Eastern Cemetery in Dundee, although without a name, it is not possible to pinpoint the grave.[v]

Dr. Templeman, the Dundee Medical Officer of Health made arrangements to have the infected sailors removed from the ship aboard the tug Advance and taken to the Smallpox Hospital at Kings Cross in Dundee. The British sailors were described as looking ‘…hardy, typical British officers,…’ bearing the marks of the disease with their overcoats buttoned up, no doubt against the cold January weather. All but one was able to walk to the van for their transfer to the hospital. The other man, who later died, was carried by stretcher and taken to Kings Cross. The Advance made further trips to evacuate two more British engineers and two more Lascar sailors, the latter presumably not in possession of overcoats but instead wrapped in blankets, to be taken away by ambulance. Later the body of the Lascar sailor who had succumbed to the disease was removed from the ship. After the patients had been evacuated from the ship, Templeman arranged for the ship to be disinfected. The remaining crew were also revaccinated.[vi]

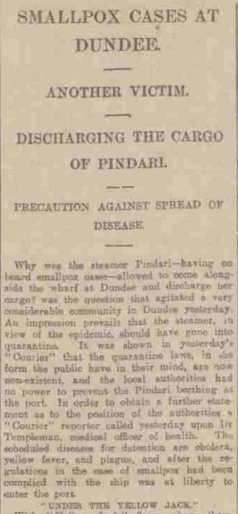

The following day, after the ship had been disinfected, the Pindari was allowed to dock at the Eastern Wharfe to discharge its cargo. Over the next few days Templeman continued to board the ship to observe the crew and another member of the Lascar crew had to be evacuated to the smallpox hospital. To avoid any risk of the disease spreading to the town a police guard was mounted to prevent the Lascars from leaving the ship. Although the Lascars were effectively imprisoned aboard ship the British Captain and chief engineer were allowed to walk about Dundee. Mr John Mitchell raised his concerns about this at the Lord Provost’s Committee on 30 January.[vii]

By the early twentieth century, arm to arm vaccination had been abandoned in favour of using calf lymph. In arm to arm vaccination Child A is vaccinated using calf lymph, the following week Child B is vaccinated using lymph taken from the vesicles (blisters) on the arm of child A, then from child B to child Cand so on. There was a risk that infections could be passed from child to child. The Royal Commission Report on Vaccination recommended in their report of 1896, that each child should be vaccinated with calf lymph, rather than by taking lymph from the arm of another child. Questions were raised about who would bear the costs of the public health measures taken to prevent any spread of the disease including purchasing the calf lymph. A local ratepayer grumbled in the press that: the Harbour Trustees collected revenues from the Pindari but the ratepayers of Dundee bore the expense. Neither could Brocklebanks be pursued for reimbursement. In her thesis, Ceri Ann Fidler comments that Indian seafarers who became unwell in Britain were expected to pay for their medical treatment from their wages.[viii] Whilst a British seaman would also be liable for his treatment, his wage rate exceeded the rates paid to Lascar crew, yet the expense was similar. Shipowners were only liable to support Lascar crew members who were destitute. As wages owed to Lascar sailors would be held in their account until they were paid off at the end of a voyage, it was almost impossible for a Lascar sailor ever to be classed as destitute.

The records of the Smallpox Hospital held in the University Archives only include those of the surviving British crew. These records are an interesting resource for both family historians and medical historians. They give the names, usual addresses, ages, and the date the patient first became infected. The vaccination status of the sailors was recorded by counting the number and a description of vaccination scars. The progress of their illness was recorded including the extent of the smallpox rash and morning and evening temperatures. All seven men had been vaccinated although judging by the description of the scars, it had been more successful for some than for others. There is also a distinct possibility that the men who had succumbed to smallpox had not been revaccinated at any time and relied on their childhood vaccination to protect them. It was recommended that revaccination was required about every ten years.

Dundee was declared smallpox free in March when the last 3 Lascar crew members were discharged from hospital and travelled to Liverpool to board a ship to return to India. Managing the outbreak eventually cost Dundee Corporation £73. 1 shilling and sixpence.[ix]

Sylvia is researching opposition to the compulsory smallpox vaccination in Scotland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, see also The Conversation.

[i] University of Dundee Archives, Reference MS 111/1/1/3

[ii] Edinburgh Evening News, 29 January 1906.

[iii] Lascar: A general term used to refer to all Indian seafarers, from the Persian-Urdu word lashkar.

[iv] Ceri-Ann Fidler, Lascars, c 1850 – 1950: The Lives and Identities of Indian Seafarers in Imperial Britain and India, unpublished thesis, University of Cardiff, 2011. P 31.

[v] Dundee Evening Telegraph, 29 January 1906; Dundee Courier, 31 January 1906.

[vi] Dundee Courier, 30 January 1906.

[vii] Dundee Evening Telegraph, 30 January 1906

[viii] Fidler, Lascars, c 1850 – 1950, p.32.

[ix] Dundee Courier, 9 March 1906.