The first of three blogs about the Alexander Low collection held by Archive Services.

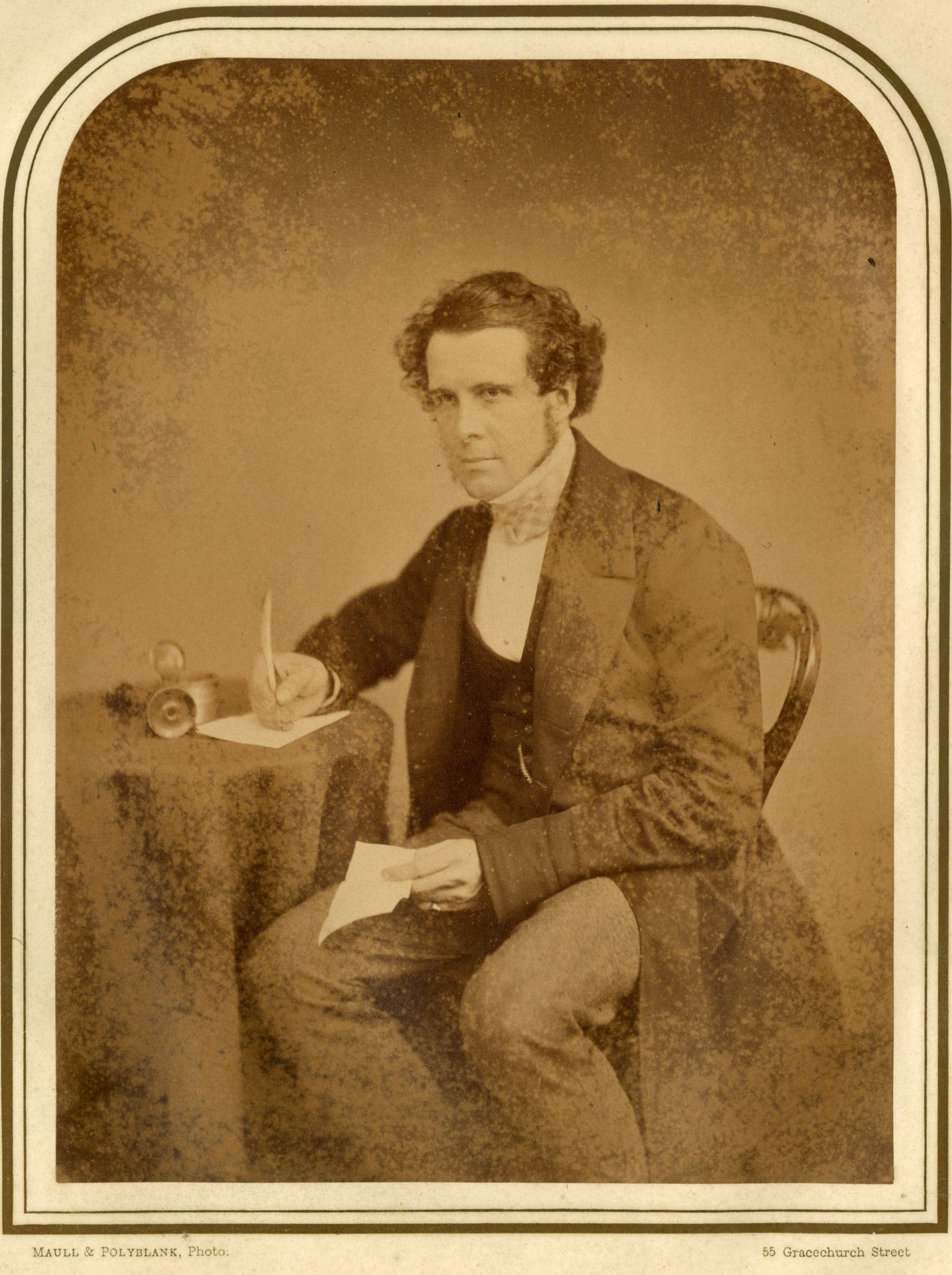

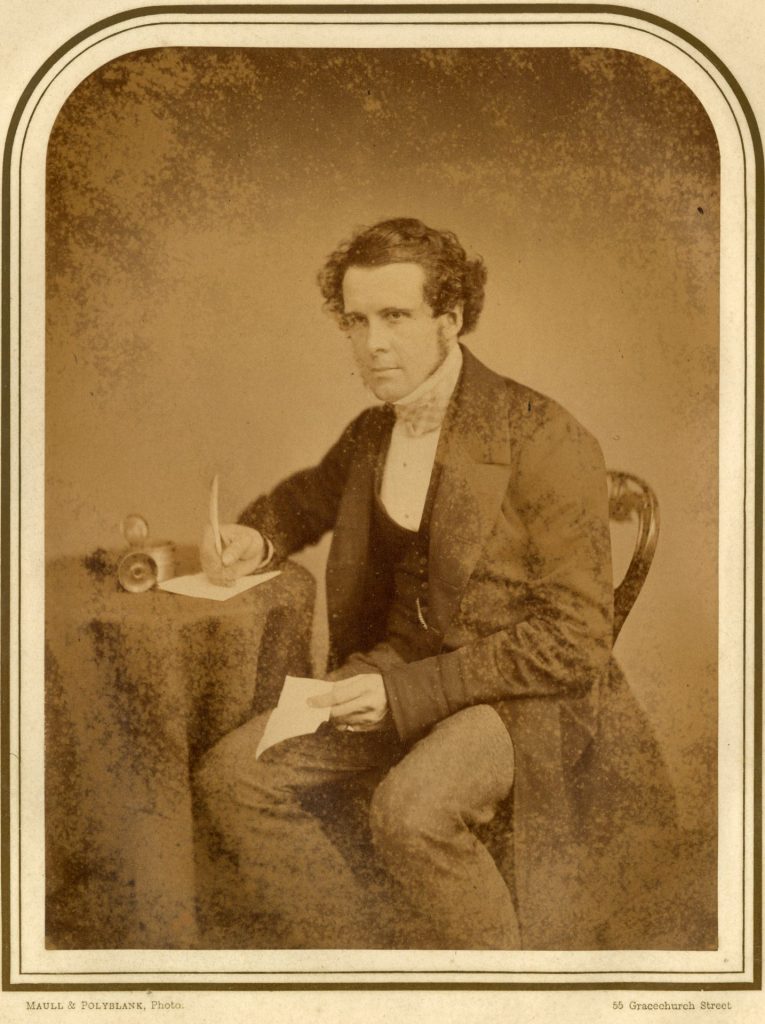

Most of us have some old family photos, letters or documents tucked away in a drawer or in the attic, but how many of us have over 20 boxes relating to eight families, dating back to 1723? Alexander Low did and decided to give them to us. The bonus is that Alex was a photojournalist and also donated the slides and prints of assignments that saw him travel across the globe in the 1960s and ‘70s. In the first of a short series, I’ll introduce you to a few of the many highlights in this substantial collection.

Alex’s international career is echoed in his family records, with many of his ancestors trading and living across the world. Although essentially based in the UK, their many letters reflect their cosmopolitan lifestyles. With today’s instant communication we often forget how letters can be rich in detail and feeling, reflecting the minutiae of correspondents’ lives as well as the personal impact of world events. Young Kenneth Low (an uncle of Alex) regularly wrote home with news of life at his school, often asking for help with his sums, and also asks for news of his brother Gerald, reported missing at the start of WW1. Gerald’s own letters from school have survived, with ones from Switzerland where he writes he is not suited for ‘a learned profession’ and has decided to go into business. Their father’s correspondence includes letters of concern and then condolence from relatives and friends when Gerald’s death was confirmed.

Correspondence can often be very revealing. It’s evident from the letters of one of Alex’s ancestors, Dr A J Halley, that he was bedevilled by financial problems. He writes to his elderly father living in Madeira, worrying that ’you do not take exercise enough, you should go about more’, but also about his ‘money difficulties’ His father writes back, agreeing that he ‘did right to break off your engagement with Miss H as it will probably be some years before you are in a situation to marry’. But just a few months later, A J informs Miss H’s father of his expected prospects, that he is going to Madeira to sort his father’s estate and hoping ‘I shall have your full and cordial consent and cooperation in uniting’ him with ‘Dearest Emmie’.

Despite his inheritance and income from his medical practice, his letters to Emmie’s father, Dr Harland, include several requests – and thanks – for financial assistance. One refers to a brougham he and Emmie want to buy, refuting his father-in law’s ‘several misapprehensions and errors’ about his financial state but admitting that his capital is ‘much smaller than my expectation led me to believe’. Defending his financial behaviour, he sends details regarding his financial situation and prospects, along with his accounts. One wonders if he ever found financial stability as just two years before he died in 1875, he wrote to the Manse at Lundie & Fowlis asking about medical opportunities in Blairgowrie.

Many letters in the collection are descriptive, such as those by A H Low, who described life in Canada in 1914, asking his mother not to disclose the location of the oil survey he was doing. Alex Low’s own correspondence features letters to his parents describing his assignments in India and across Argentina – which he was keen to leave for the USA. One of the earliest letters in the collection is by Alfred Chabot to his half-brother P J Chabot, describing his horrible voyage to Falmouth in 1838; the food was rotten and the weather stormy. Remarkably, a recent email from Australia asked for a copy of this letter. Apparently, they’d been told about the collection and as Alfred was an ancestor, they hope the letter will tell them a little about his life prior to his family’s emigration as ‘free settlers’.

A most interesting series are the letters between the West branch of the family and which vividly bring them to life. Colonel Matthew Richard West married Evaline Lucas in 1873. He served in India and Ireland, but suffered constant ill-health, writing to Evaline in 1884 ‘I ought to pull round, with a true devoted wife, doing all she can, & try to be some use as a husband & a father, instead of as at present, useless to myself & everybody else’. Twenty years later, while being treated in Switzerland and on his death bed, his doctor expresses concern about Evaline’s letters, suggesting they are not welcomed by her husband. At first, I wondered if this suggested marital discord, especially as no later correspondence between them survive. But it’s probable her letters weren’t welcome because they contained news of their son George; his own letters and those about him chart a sticky career in the army and increasing signs of deterioration in his mental health.

The letters about George, and particularly between George and his mother, chart his life from a schoolboy. A letter about George’s progress at school notes, ’he completed under circumstances calculated to make one forget everything one ever knew’, which is intriguing. However, George passed his exams and following in his father’s footsteps, joins the Army. But by 1897 he’s in deep trouble, shown by letters sent to his mother expressing concern over George’s dishonoured mess cheques and the likelihood of being dismissed from the army unless he transferred abroad. The following year, George is writing to his sister from Sierra Leone, after being advised to join the Garrison Artillery ‘where he might determine to live less expensively’. After Sierra Leone, where his commanding officer wrote praising his service, he moved to Nigeria. It’s not clear what happened there, but Evaline had evidently written directly to the Prime Minister, as there’s a reply from Downing Street confirming that ‘Captain GA West will be returning to England from Southern Nigeria.’

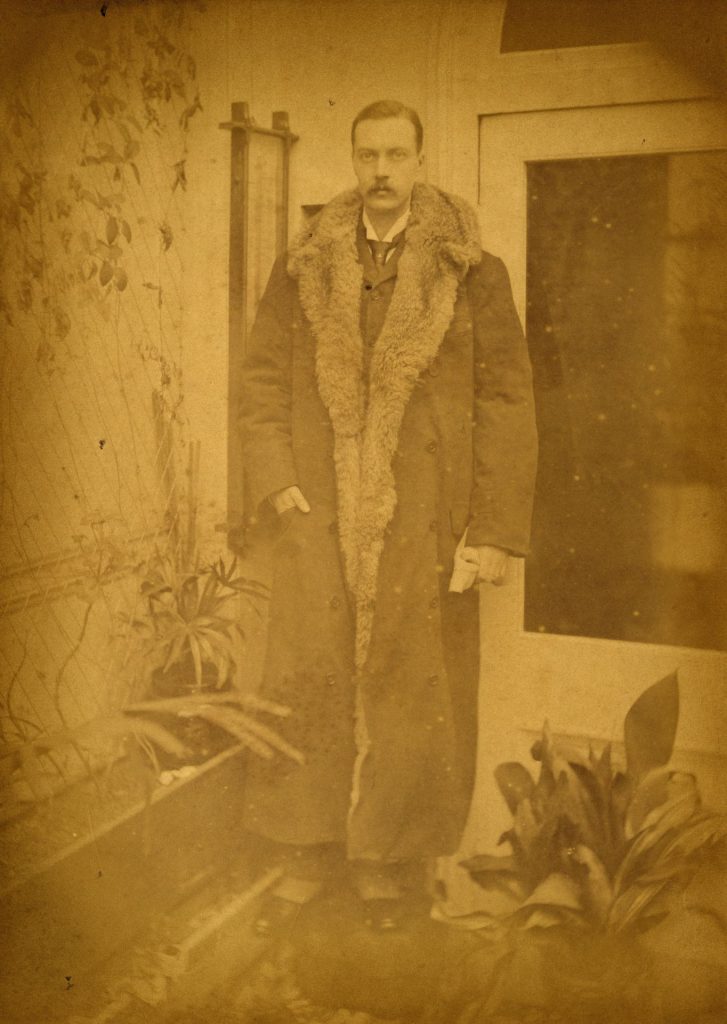

By 1905, George is in Russia, attached to the consulate in Archangel. Traveling to places like St Petersburg and Sebastopol, he writes to his parents about his confidence in learning Russian and about refers to the tense situation between the Czar and the Russian workers. By 1912, George is back in England refuting accusations that he is ill because ‘I avoided people’ or that ‘the whole British colony were wishing to kill me’, and desperate to return to Russia.

We don’t know how George fared between 1914-1918, but after the war, George evidently travels to Salzburg, Biarritz and Sweden, writing to his widowed mother who has settled in France. Many of these letters describe where he stays and the people he meets. Financially supported by Evaline, his expenses are a constant theme. He also seems to staying at health spas, where his treatments appear to be constant head and body massages.

By 1926 there are letters to Evaline, initially from his landlady in England and then by a doctor who suggests his admittance to the Priory. George sends her a statement which charts his episodes and breakdowns since 1904, but Evaline resists his confinement in any asylum. For months George receives treatment in the homes of at least three private doctors, who send letters on his progress. On settlement of his bill, George’s last doctor admitted that he ‘would not take on such a case again’, even if he was ‘paid properly’ for his care, which he evidently thought he wasn’t.

There are no more letters after the spring of 1928 and two years later both Evaline and George’s sister are dead. But one of the consequences of owning such a collection is the irresistible temptation to do further research. Luckily for us, that’s just what Alex Low and his partner Anna did before he sent the collection to us. From their research, we learn that with no surviving family, George was admitted to Holloway Sanatorium. Payment for his care is through a cousin, initially supervised by Alex’s grandfather. There is one letter in the collection from George’s cousin, worried about a letter received from the Sanatorium in 1933 which noted that ‘George must be a paying asset’ – an echo of his last doctor’s comments. George died alone in Holloway Sanatorium in 1951.

Many letters in the collection are simple records of personal and family news, while others relate to business and legal matters. But together they tell the stories of people’s lives and their relationships with family and friends, a rich source of insight and understanding of past lives.

Search the full description of Alex Low collection for more letters.

Jan Merchant, Senior Archivist.