This blog post was written by Medical Students, Kirsten Healey and Hannah Dalioui as part of their Selected Student Component working with the collections at the Tayside Medical History Museum. SSCs are an important part of medical training aiming to establish a foundation for lifelong learning and explore new ways of communicating information in non-clinical settings.

Together with the University of Dundee Museums team, they designed a new mini-exhibition titled Maws & Bairns- Maternal and Neonatal Care and produced two blog posts highlighting some of their favourite artefacts in their exhibition.

Objects used in clinical practice rarely have the stories behind their discovery told. While putting together the exhibition on maternal and neonatal healthcare we looked at two objects in the Tayside Medical History Museum which we recognised from our teaching and investigated the stories of how they came to be.

Gosset’s Icterometer

The first object we were intrigued by and chose to research further was a Gosset Icterometer, a screening tool for jaundice developed by Dr Issac Henry Gosset (1907 – 1965). Jaundice is a yellow discolouration of the skin that occurs due to high levels of bilirubin in babies. Although jaundice occurring after 24 hours of age is reasonably common, if it occurs sooner than this there may be a life-threatening cause behind it. Quick identification of the condition is crucially important to delivering fast treatment and saving lives.

During his career, Gosset held several important roles including Casualty Officer at the British Postgraduate Medical School and Senior House Physician at Radcliffe in Oxford. In 1940 he volunteered for the Royal Air Force where he worked as a Medical Specialist before becoming Wing Commander. He became the Senior Medical Specialist and was in charge of the medical division of one of the largest RAF hospitals. He left the RAF in January 1946 and began a career as the first consultant paediatrician in Northampton where he helped with the planning and opening of a premature baby unit there in the 1950s. The special care unit was renamed the Gosset ward in honour of his work in neonatal care.

Gosset developed this icterometer in 1954 as a tool to help doctors quickly identify jaundice. The icterometer consists of plastic strips painted different shades of yellow which can be compared with the colour of the baby’s skin. It works by pressing it down on the baby’s nose and matching the colour seen to one of the five strips. The icterometer had some limitations as it was not highly accurate and if there was suspicion of something concerning, blood test were required to diagnose the cause. However, being so quick and easy to use it was especially important in identifying jaundice in new-borns and proved more reliable than judging by eye. Although simple in design, this small Perspex comparator has potentially lifesaving effects.

Following his death, Gosset’s family was sorting through his letters and discovered that many other doctors across the globe were enquiring how they could get an icterometer of their own. By 1961 there were over 1000 sales. Although no longer used in UK medical practice it is still used around the world, and is an important object in the history of neonatal care.

Ergot and Ergometrine

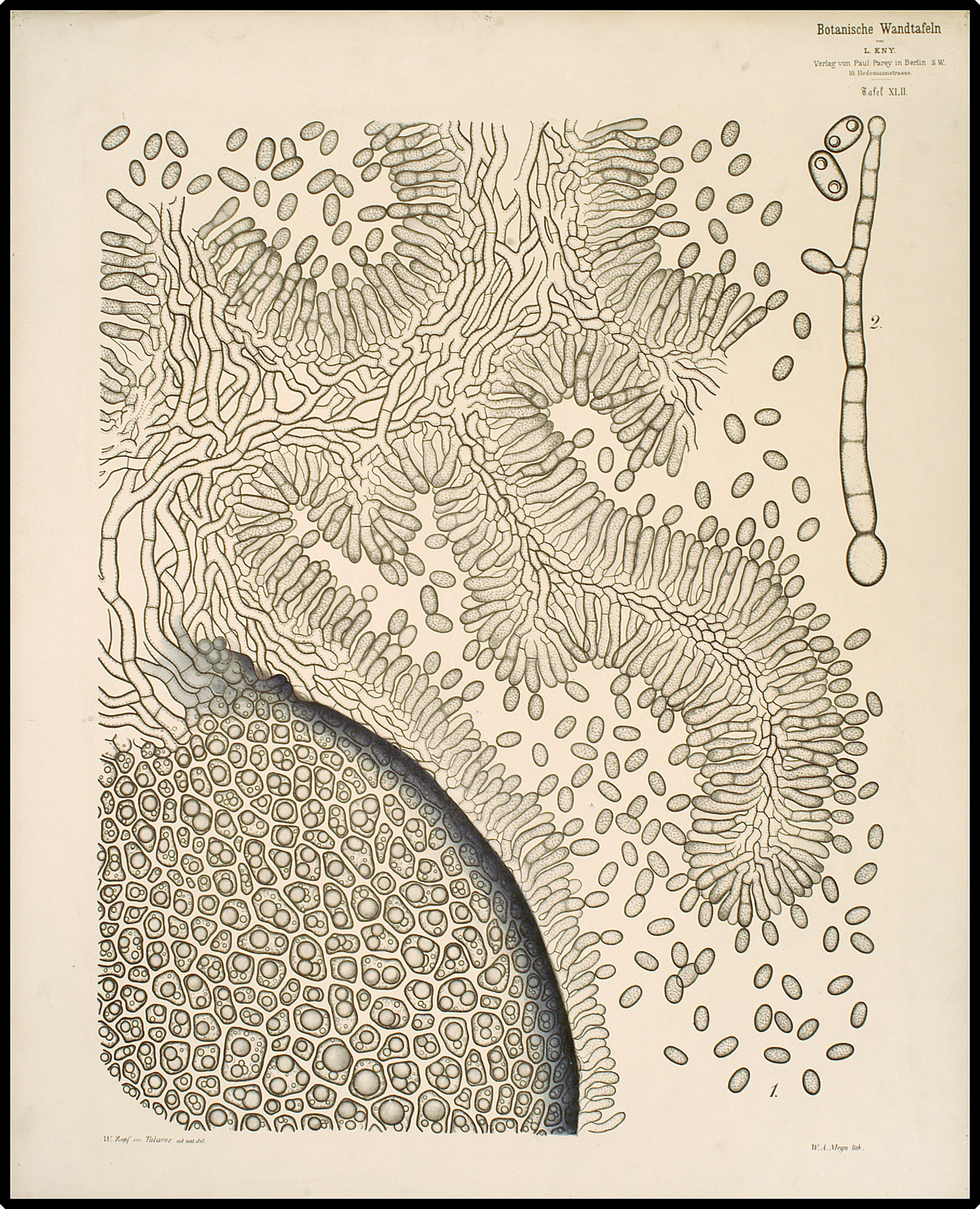

Our second object of interest was a wooden box sitting on a shelf of medicinal plants. The box contained ergot of rye (a plant disease caused by the fungus Claviceps purpurea). We were told it was linked to ergometrine, a drug which we had heard about in teaching but hadn’t considered where it had come from.

While it had been known since the 16th century that ergot had the power to prevent heavy bleeding in periods and childbirth by narrowing the blood vessels and causing uterine contractions, it was not used in clinical practice due to the unpredictable effects of ergotism.

Ergotism had two main manifestations: gangrene (referred to as chronic ergotism) and convulsions (acute ergotism). In acute cases, ergotism is often accompanied by hallucinations and has been suggested as the cause behind the so called ‘Dancing Plague’ of 1518 where around 400 people started dancing uncontrollably in Strasbourg, France. Dozens of dancers died from strokes, heart attacks and exhaustion. It has also been proposed as a potential factor behind witch trails in the 16th and 17th centuries due to the hallucinations and convulsions it can cause.

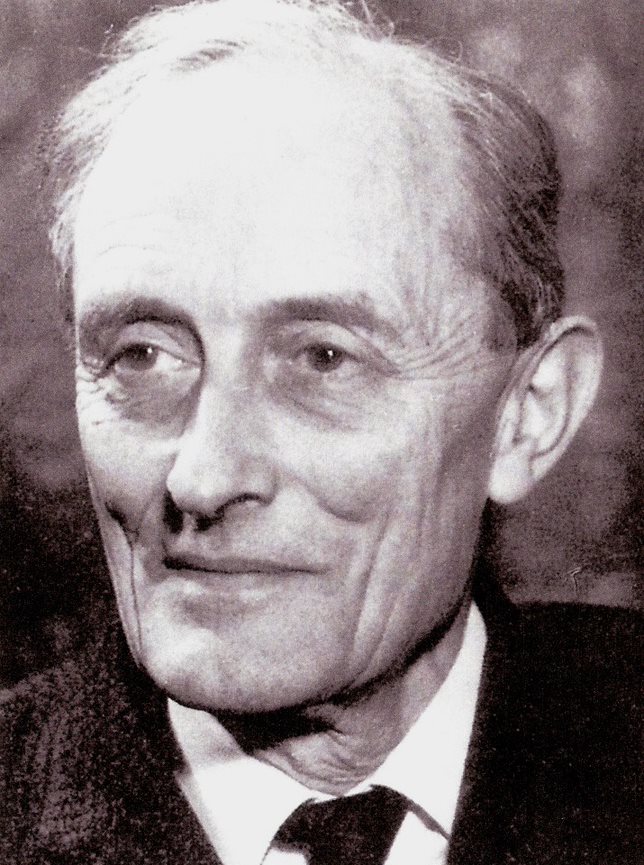

The story of how this fungus with potentially dangerous and unpredictable effects was transformed into a lifesaving drug centres around Montrose born John Chassar Moir (1900-1977). Moir was a distinguished professor of obstetrics and gynaecology in Oxford. In the 1930s he led a team of researchers that discovered ergometrine. Previously it was thought that the alkaloids of ergot, ergotoxine and ergotamine were responsible for the contractions, but Moir showed that this effect was actually due to the aqueous extract of ergot, from which he and Harold Dudley later isolated the active principle ergometrine. All of this was accomplished at a total cost of six shillings, a feat Moir proudly attributed to his Scottish inheritance!

The identification of ergometrine, which by preventing and controlling postpartum haemorrhage, has saved countless lives and is undoubtedly linked to the improvements in maternal mortality in the 20th C. Moir also achieved distinction for his repair of vesicovaginal fistulae, a distressing condition where urine continually leaks through the vagina. His BMJ obituary described him as “a man who did more than anyone living today to save the lives and relieve the miseries of women”.

Having heard about these objects in our clinical teaching it was interesting to find out more about how they were invented and think about how other equipment and medication we use today first appeared.

You can see the Icterometer, ampoules of Ergometrine and other objects selected by Kirsten and Hannah in the Maws & Bairns – Maternal and Neonatal Care exhibition case on Level 8 of the Medical School next to the elevator.

[1] Gosset wrote about his Icterometer in The Lancet in 1960 explaining how it was used and made, as well as acknowledging it’s limitations. You can read what he said here.